Uncommunicated expectations are preconceived resentments

Ain’t it the truth

Author: Sysop

Ain’t it the truth

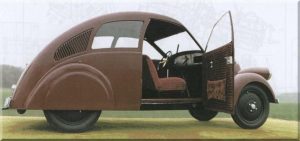

The Volkswagen, or “People’s Car,” that so many millions have known for more than half a century had its genesis in Nazi Germany. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, who designed the Volkswagen, had to share the concept with none other than Adolf Hitler. And though the Volkswagen may have first been intended for use as a civilian recreational vehicle, it was quickly transformed into three basic military iterations: the Kommandeurswagen (commander’s car), Kubelwagen (bucket car), and Schwimmwagen (amphibious car). The VW’s transformation into a military vehicle was a rapid metamorphosis over which Porsche had no control.

The original concept for a German Kleinauto (small car) was in part a response to the phenomenal success of the Ford Model T. The German motorcycle company NSU decided to venture into the small-car business and hired Porsche to design such a car. The prototype was known as the Type 32 of 1932, and was only one of numerous prototypes before the actual Volkswagen went into series production. Porsche had considerable experience in automotive design. Born and educated in the Czech Republic, his mentor was Hans Ledwinka, designer of the early rear-engine air-cooled Tatra. Porsche believed in Ledwinka’s design. In 1900, at the age of 25, he showed his Lohner-Porsche-Electrochaise, powered by electric motors, causing a sensation at the Paris World’s Fair

In 1905, Porsche joined the Austro-Daimler Company and designed his first race car, the Prince-Heinrich-Wagen. Through racing-car design, Porsche realized early on the importance of aerodynamics, and this influenced most of his later automotive designs. Wind-resistance tests helped him create highly successful racing cars for Auto-Union. Before starting his own design firm in 1929, Porsche worked for Daimler-Benz, helping develop the famous SS, SSK, and other Mercedes models.

When Hitler took power, Porsche announced his concept of a small, inexpensive car at the 1933 Berlin Auto Show. At the show, Hitler promised to transform Germany into a truly motorized nation. Porsche and Hitler met in May 1934 to discuss plans for the “People’s Car.” Porsche outlined the specs he had in mind. The car would have a one-liter displacement air-cooled motor, producing approximately 25-brake horsepower at 3,500 RPM, weigh less than 1,500 pounds, with four-wheel independent suspension to reach a top speed of 100 kilometers per hour. Hitler added specs according to his own vision: the car was to be a four-seater, get 100 kilometers per seven liters of gasoline, and maintain 100 kilometers per hour. Porsche proposed that the car be priced at around 1,550 marks ($620 at 1934 exchange rate).

Hitler limited the price of the Volkswagen to 900 marks and gave Porsche only 10 months to build a prototype. Beating out other proposals, Porsche and his design team began building three prototypes in a garage at his home near Stuttgart. Hitler monitored the progress impatiently, then found out that Porsche was a Czech citizen. Dismayed, he quickly rectified the political problem by formally converting Porsche’s citizenship.

The three prototypes, finished in 23 months, were successful from the beginning, once the front torsion bar suspension was “debugged” to make the twisting bars stronger and more flexible. Porsche, with his design team, which included his son Ferry, visited the United States to observe how Ford, Chevrolet, and Oldsmobile were mass-producing their cars. Hitler encouraged Porsche to go on the transatlantic journey, thinking that he would be well received by Henry Ford. During his earlier imprisonment, Hitler had read Ford’s biography while writing his own Mein Kampf, and he believed he knew where Ford’s sympathies lay.

The road tests of the VW prototypes began in October 1936. At first, different motor designs were tried out, including a two-cycle and two-cylinder version, until Porsche settled on the “boxer” four-cylinder, four-stroke design. The essence of the boxer design was that all cylinders were arranged in a flat bank with all crank arms in one plane. The fan-assisted, air-cooled design was virtually immune from both overheating and freezing, unlike liquid-cooled engines. Simplicity and accessibility to various components was another advantage. The chassis and suspension of the Volkswagen used a basically flat platform with a central tube backbone that held the shift linkage and hand brake cable. The VW’s suspension consisted of crank-link front and swing rear axles, with the wheels suspended individually. Instead of the usual leaf or coil springs, the VW used torsion bars, a revolutionary concept at the time.

he relative success of the three VW prototypes was a minor achievement in comparison to the goal of mass-producing such cars by the millions. Hitler, vowing to out-produce Ford in the United States, became agitated over what he called the industry’s procrastination. On February 28, 1937, he warned during a speech that if private industry could not built such a car, it would no longer remain private industry. These histrionics foreshadowed what would face the Volkswagen company within a short time.

At the 1937 Berlin Auto Show, Hitler visited the exhibit where the latest automotive achievements were on display, among them the small Opel P-4, which was selling for 1,450 marks. Hitler listened to Adam Opel explain that this was his version of the Volkswagen, upon which the Führer stormed off angrily, warning that no private companies would be allowed to enter the small-car market on a competitive basis. Volkswagen was to be Hitler’s offspring, and nobody except Porsche and his team were to have a hand in its cultivation. Hitler was using the “People’s Car” to utmost political advantage. The Nazi brass formed a new company called Gesellschaft zur Vorbereitung des Volkswagens, funded by the German Labor Front. Now Porsche, his hands no longer tied financially, threw himself into the project like the dedicated engineer and businessman he was. A small factory was set up in Zuffenhausen, near Stuttgart, and 30 more prototypes were produced. Soon another 38 were built. Since few people in Europe fully understood the industrial science of automobile mass production on the scale that Hitler wanted, Porsche and his team returned to the United States to recruit engineers and executives and buy more equipment.

At the same time, the German Labor Front devised a scheme by which workers could buy a Volkswagen in advance. Through the Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) organization, which sponsored all sport, travel, recreation, and leisure activities for industry workers, money was collected on a layaway basis. By the time World War II began when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, a total of 210 KdF Volkswagen sedans had been built. Only two prototype units were military versions. The rest of the KdF sedans were allocated to military officers as personal cars. Hitler was given the very first convertible Beetle built in 1938. Photographs of the vehicle were published in Der Adler.

The Kubelwagen (Bucket Car) idea stemmed from a meeting on January 17, 1938, between the SS-Fahrbereitschaft VW director, the director of Heereswaffenamt (Army Weapons Office), and other HWA officials. The purpose of the meeting was to see how the KdF Volkswagen could be turned into a military vehicle. Another meeting nine days later gave the Porsche company free reign as to how to achieve such a design. It was not until the beginning of November 1938 that the first Kubelwagen was shown. The initial rear-wheel-drive prototype was called the Type 62 and was compared to the standard HWA four-wheel-drive, four-wheel-steer military personnel car. The new design was met with approval, excepting the sheet metal, which was deemed too “civilian-looking.” Further tests were also favorable, and the body was redesigned. Compared with the KdF sedan, larger tires were used, the rear track was widened, and ground clearance was increased.

Aside from the redesign of the sheet metal, one of the first military requirements for the Kubelwagen was that it would be able to run in first gear at 2.5 mph, the walking speed of a German soldier with backpack. The standard KdF-wagen’s first-gear cruising speed was twice that—about 8 kph or 5 mph. At first a lower transaxle gear ratio was used, but this was still insufficient, so another alternative was adopted. By using a reduction gear at the end of each swing axle, the right speed was achieved. It also created more torque and provided a higher ground clearance for the VW “stand-alone” chassis, which would become a versatile platform for a variety of applications. Later, this reduction gear was used in VW buses and vans.

The Porsche team reluctantly redesigned the VW for its new military roles without having to redesign the drive-train, except for increasing engine displacement to 1.13 liters, which obtained 24.5 bhp. When an advisory contract with Daimler-Benz expired in 1940, the Porsche Company was recommended to the HWA to go into tank design, and Porsche would soon find himself as head of the Panzer Commission. At the same time, the Führer pushed for the military adaptation of the VW. Off-road capabilities were improved with the Type 82 Kubelwagen, which incorporated the crown-wheel- and-pinion gear reduction. Larger off-road tires were used and ground clearance was increased once more. The two Kubelwagen prototypes had bodies built by Ambi-Budd in Berlin in December 1939. Upon its acceptance as an official military vehicle, the Kubelwagen received the official designation of Le PKW-K1 Type 82.

The giant Wolfsburg factory, with its newly built “Strength Through Joy Town,” was converted in 1940 to build war materiél. Large areas were turned into repair shops for the Junkers Ju88 bombers. Also, large quantities of mines were to be produced, as well as BMW aircraft engines. Toward the end of the war, V-1 bomb rockets were also assembled there. Manufacture of the “war contingency alternative” to the People’s Car, the Kubelwagen, the Porsche version of the German Jeep, also got under way. This design was completely independent of the four-wheel-drive vehicle that the German Heereswaffenamt had built, which was much more expensive than the Kubelwagen. In January 1940, another version of the KdF, the 4×4 Type 86, was put through comparative testing at Eisenach. However, only two prototype vehicles of the Type 86 were ever built. The 4×4 continued as the Type 87.

As the Kubelwagen was being developed, on July 1, 1940, the Porsche Company was given a contract to build three variations of amphibious cross-country vehicle prototypes for the sum of 200,000 marks. The result, called the Schwimmwagen, was designated Type 128. The first prototype was based on a Type 82 Kubelwagen that had its doors welded shut. The entire body was sealed water-tight, and a propeller that folded down to engage with a shaft extension from the engine crank moved the Schwimmwagen through the water. The Type 128 used the same 1.13-liter engine as in other military versions. It was capable of 10 kph in calm water, and calm water was imperative because the all-in-one design was heavy enough to be easily swamped by the smallest of wakes or waves.

Because of the Nazi hierarchy’s lack of rapid decision making, production of the Kubelwagen was at an impasse until early 1940, when other comparison road tests proved the Kubelwagen to be superior to the HWA vehicle in many ways and cheaper to build. More than a year after the war started, production of the Kubelwagen finally ensued. The VW sedan with four-wheel-drive was called the Type 87. Running gear of the Type 87 was used for the Schwimmwagen Type 128 and Type 166. All VW 4x4s used the Kubelwagen chassis and 1131-cc engine.

In early December 1940, the Waffen-SS and the Porsche team conferred. The military wanted a small armored car, and on December 22 a contract was awarded. By January 14, 1941, the contract for the Type 823 armored Kubelwagen was amended to eliminate the armor and create another version called the Type 821, which was to be a radio car. Another version, an ambulance, was called the Type 822. Mockup prototypes of each were built in 1941.

wo other iterations based on the Type 82 Kubelwagen were an intelligence car and a repair car. In addition, there were also versions with rail wheels and other special equipment, but these were built as one-off or in very small numbers. The VW platform was proving itself to be efficient, inexpensive, and, above all, extremely versatile. It was particularly well suited for off-road desert conditions, and approximately half of the vehicles produced were used very effectively by General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. The “tropical” version included Kronprinz balloon tires without longitudinal treads to trap sand and soil, special air filters as well as a second fuel tank, intended for drinking water but used for gasoline to double the range in areas where refueling was a drastic problem.

In the desert, the VWs far out-performed heavier Allied vehicles as water-cooled engines overheated and trucks bogged down in the sand. The VW was amazingly effective in North Africa, and decades later this capability was proven again in the form of the “dune buggy” and “baja bug” used in professional racing under similarly harsh desert conditions. With partially deflated rear tires, the traction of the quick, rear-engine vehicles was impressive in off-road conditions of all kinds, including the snow and ice encountered during the invasion of Russia. In freezing temperatures the air-cooled engines performed even better. The problem was there were just too few of the vehicles.

From 1940 to 1943, a total of 630 KdF sedans were also built with the designation Type 60 at Wolfsburg. These had a “civilian” (i.e., pre-Kubelwagen) chassis and used the slightly smaller 986-cc engine. An ambulance version was designated Type 67. One-off versions included a pickup truck and delivery truck. Also built were 564 Type 87 sedans, the latter with the 4×4 Kubelwagen chassis. Other one-off variations included a box van (Type 81) and open truck (Type 825).

The Type 82E Beetle, like the Type 82 Kubelwagen, had the additional gear reducers in each rear wheel and used larger 5.25×16 off-road tires. These Beetles were delivered in matte black, to be painted by the Wehrmacht with tan or camouflage colors. Delivered to the SS, these were called Type 92SS and included such items as rifle racks in the rear interior, a bracket-held submachine gun in the right front interior, slide-out desk from the glove compartment, and first aid kit.

At about the same time as the Waffen-SS group ordered Kubelwagens, the HWA ordered 100 Type 128 Schwimmwagens. These were thoroughly tested and the Porsche firm was given an extensive contract to build the amphibious off-road vehicles. Another version of the Schwimmwagen, the Type 138, was dropped, but the Type 166 and Type 177 were slated for manufacture. The latter designation was to have a five-speed transaxle, which never went into production. By the end of the war, 14,276 Schwimmwagens were built, almost all assembled at the Wolfsburg factory with bodies supplied by Ambi-Budd from Berlin. Sixty-six percent of all the Schwimmwagens were the Type 166, which was smaller and lighter than the Type 128. Most of them were supplied to Waffen-SS divisions after the Type 166 went into production in 1942. Officers of advance units used them to move across country, ford rivers, and carry out reconnaissance by water, but many officers used them as platforms for duck shooting.

One of the more unusual theaters of operation for the VW during World War II was in the service of the Office of Colonial Policies. This German military section sent Type 82 E VWs and a Kubelwagen, along with a supply truck, on a trip to Afghanistan in June 1942. The vehicles were specially prepared for the trip. They were finished in high-gloss light paint and had chrome bumpers and door handles, ostensibly for protection against sand storms and oxidation. They also had auxiliary air vents in front of the windshield for ventilation, as well as extra louvers in the bulkhead between interior and engine for better cooling. Special air filters and off-road tires were also part of the equipment. The Office of Colonial Policies wanted to equip civil administrations with these types of vehicles.

Starting out in Berlin, the column drove through Dresden, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, and Constanza on the Black Sea. They were then loaded on a Romanian freighter. After a sea voyage from Istanbul to Trabzon, the vehicles reached Teheran and then were driven to the Afghanistan border. Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop insisted that the Afghan government collaborate with Germany to battle British forces on the Eastern Mediterranean and in India. When Iran, on the side of Germany, was occupied by British and Russian troops, the order was given to destroy the VWs so that they would not fall into Allied hands.

One of the more unusual theaters of operation for the VW during World War II was in the service of the Office of Colonial Policies. This German military section sent Type 82 E VWs and a Kubelwagen, along with a supply truck, on a trip to Afghanistan in June 1942. The vehicles were specially prepared for the trip. They were finished in high-gloss light paint and had chrome bumpers and door handles, ostensibly for protection against sand storms and oxidation. They also had auxiliary air vents in front of the windshield for ventilation, as well as extra louvers in the bulkhead between interior and engine for better cooling. Special air filters and off-road tires were also part of the equipment. The Office of Colonial Policies wanted to equip civil administrations with these types of vehicles.

Starting out in Berlin, the column drove through Dresden, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, and Constanza on the Black Sea. They were then loaded on a Romanian freighter. After a sea voyage from Istanbul to Trabzon, the vehicles reached Teheran and then were driven to the Afghanistan border. Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop insisted that the Afghan government collaborate with Germany to battle British forces on the Eastern Mediterranean and in India. When Iran, on the side of Germany, was occupied by British and Russian troops, the order was given to destroy the VWs so that they would not fall into Allied hands.

Yet another metamorphosis of the VW took the form of a half-track. The Porsche firm embarked on building VW-derived “People’s Tractors,” with this series culminating with the Type 151-1 half-track. It was also called the Kettenlaufwerk and was used successfully in small numbers both by the Afrika Korps and in Russia. Again using the VW platform, the Type 151-1 had three drive wheels of equal diameter on each side that powered the caterpillar tracks. Front wheels were of standard disc type used only for steering, as on nearly all half-tracks. It was used as a personnel carrier and tow tractor.

The Wolfsburg factory was heavily damaged by Allied bombing, but from May 1945 to the end of 1946, limited production continued with left-over parts. According to British military sources, during this time at least 1,785 VW Beetles were built, 977 with the KdF Beetle body and Kubelwagen chassis. Left-over Kubelwagens were also assembled when the factory was rebuilt under British Major Ivan Hirst. There were at least 10 variations of the Beetle with new designations and at least four for the Kubelwagen. The Ambi-Budd Berlin factory, now located in the Russian sector (soon to become part of East Germany) where Schwimmwagen and Kubelwagen bodies were pressed, was destroyed, so no additional vehicles with these bodies were assembled after 1946. In 1947, civilian VW Beetle production resumed. It was essentially the same Type 60 of prewar configuration.

At war’s end, Ferdinand Porsche was arrested by the French military and accused of war crimes. However, he was found to be not personally responsible for the use of slave labor, and through the efforts of his family he was released. He and his son subsequently finished development of the Porsche sports car, which had first been built as a prototype before the war. The first 50 units were built in Austria in 1948, after which time Porsche’s Stuttgart factory began building the Porsche 356 in 1950.

The VW Kubelwagen of WWII was resurrected in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the form of the VW “Thing,” designated the Kubel 181. It was first developed for the German military and used by the Technische Hilfswerke, postal system, fire departments, and border patrol, gaining a modicum of popularity in the United States with assembly at the VW Puebla factory near Mexico City.

Although VWs in military guise were built in relatively small numbers, they had a noticeable impact during World War II, proving the versatility of the original design. Due to the politics of the day, the VW was underutilized and never achieved the universal acceptance of the American jeep. Once the war was over, though, the civilian, rear-engine, air-cooled VW was a great success for another half-century, assembled and exported around the world.

Originally Published in 2018.

This article by Albert Mroz originally appeared on the Warfare History Network. It was originally published in 2018 and is being republished due to

Thank you!

The short, Tormented Life of Computer Genius Phil Katz

By Lee Hawkins Jr. of the Journal Sentinel staff Last Updated: May 20, 2000

Then he was found dead April 14, Phil Katz was slumped against a nightstand in a south side hotel, cradling an empty bottle of peppermint schnapps.

The genius who built a multi million-dollar software company known worldwide for its pioneering “zip” files had died of acute pancreatic bleeding caused by chronic alcoholism.

He was alone, estranged long ago from his family and a virtual stranger to employees of his own company, PKWare Inc. of Brown Deer.

He was 37.

It was an ignominious end for a man who created one of the most influential pieces of software in the world – PKZip – and it attracted the attention not only of the techno-faithful but of the mainstream press across the nation.

Katz’s inventions shrink computer files 50% to 70% to conserve precious space on hard disks. His compression software helped set a standard so widespread that “zipping” – compressing a file – became

a part of the lexicon of PC users worldwide.

But the riches his genius produced were no balm for what had become a hellish life of paranoia, booze and strip clubs. Toward the end, Katz worked only sporadically, firing up his computer late at night, while filling his days with prodigious bouts of drinking and trysts with exotic dancers.

Katz owned a condominium in Mequon but rarely stayed there. Desperate to avoid warrants for his arrest, he bounced between cheap hotels near the airport. He got his mail at a Mailboxes Etc. store in Franklin.

“This guy did not have one friend in the world. I mean, a true friend,” says Chastity Fischer, an exotic dancer who often spent time with Katz and was one of the last people to see him alive. “Just imagine having nobody in your life. Not anybody to call. Nobody.”

High School Outcast Phil Katz was a quiet, asthmatic child whose athletic pursuits as a kid went no further than riding dirt bikes in his Glendale neighborhood.

A 1980 graduate of Nicolet High School, Katz was a “geek” long before that term was linked with dot-com companies and piles of money.

“He was an outcast, definitely someone who was picked on,” says Rick Mayer, who graduated with Katz. “He spoke in a somewhat nasal tone. He was short, and, well I don’t want to say homely, so I’ll say he was plain looking.”

After hearing of Katz’s death, Ray Fedderly, a Milwaukee cardiologist who sat next to Katz in high school honors math and physics classes, opened his high school yearbook and found an angst-ridden message.

“I enjoyed working with you in mathematics and physics classes through the four terrible, long, unbearable, tortuous, but wonderful years at Nicolet,” Katz wrote. “I hope your future is bright and

your life is happy (if possible). May a calculator bring great happiness to you.”

“If I were a physician as I am now when I was 18, I would have known what to do with that note,” Fedderly says. “I now know that that was a call for help. That was not a joke.”

A loner by nature, Katz gravitated to analytical pursuits. Katz and his father, Walter, spent weekend afternoons playing chess and evenings writing code for programmable calculators in the days before PCs forever changed computing.

Since programmable calculators had very little memory, Phil and Walter had to work very efficiently.

“The earliest program I remember him writing was a game program that dealt with landing on the moon,” says Brian Kiehnau, Katz’s former brother-in-law who met him in 1977.

“It was very crude and simple, but it was complex for what he had in terms of hardware. He got real good at optimizing programs, and he learned to get the job done with the least amount of instructions and running times.”

In 1980, Katz entered the computer science program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Around the same time, Walter and Hildegard Katz bought Phil his first computer, an original IBM PC. It had two floppy drives, a monochrome monitor and 64K of memory, an astoundingly small amount compared with today’s machines.

Once he got the PC, Katz started writing programs, spending most of his free time on electronic bulletin board services, the precursors of the Internet.

The services quickly became Katz’s social circle, a place where he hooked up with others who understood his sophisticated programming techniques and shared his passion for computers.

Gradually, Katz developed a fondness for sharing information on the services, since interacting with others helped make his programs better. Those experiences would influence Katz to embrace the “shareware” approach to distributing PKWare’s software. With shareware, users try a product, and if they find it valuable, pay the person who created it. In the case of PKWare, users paid $47 and received a manual and free upgrades. “He spent many, many hours talking to people and helping people. He would go to computer user groups and spend hours with them,” Hildegard Katz says. “He was very, very, giving. This was his great love.”

But in the spring of 1981, tragedy overtook the family, and things would never be the same for Phil Katz. Walter, 55, plagued by recurring chest pains, underwent open heart surgery. Within hours, he was dead.

Phil Katz took his father’s death very hard. Years later, in the haze of his drinking binges, Katz told Fischer how the loss had affected him.

“It tore him up inside when his father died. One time we went to his grave,” Fischer says. “He’d always say that when his father was alive they’d go fishing and do man things.” Walter’s death drove his son further into solitude and deeper into a one-on-one relationship with his computer, say friends and family members.

Writing Programs at Night Katz graduated with a computer science degree in 1984 and was hired as a programmer for Allen-Bradley Co. He wrote code to run “programmable logic controllers,” which operate manufacturing equipment on shop floors worldwide for Allen-Bradley’s customers.

Katz left Allen-Bradley in 1986 to work for Graysoft, a Milwaukee-based software company. He spent evenings holed up in his bedroom writing his own programs.

His project: An alternative to Arc, the then-common program for compressing files. Using algorithms, Katz wrote programs that imploded information by telling it, for example, to take every “a-n-d” out of text. That would eliminate every “and,” “hand,” and “sand.” A good program takes out these and thousands of other combinations of letters and restores them when needed.

Katz bounced early versions of the software, called PKArc, off his buddies on the bulletin boards and spent countless hours refining it. By 1987, the software had created such a buzz online that PKArc started to steal market share from Arc’s creator, System Enhancement Associates of New Jersey.

“I got a check in the mail and I thought, ‘Gee!’ that’s pretty neat,” Katz said in a 1994 interview with the Journal Sentinel. “Then over the next few months, I got more checks in the mail.”

He turned to his mother for help.

“People kept calling him saying, ‘We would like to use your software, and we want to pay you money for it,’ ” Hildegard says.

Katz left Graysoft in 1987 to strike out on his own. PKArc’s sales dwarfed his Graysoft salary, which was in the low-$30,000 range, says Steve Burg, a former Graysoft programmer who joined PKWare in 1988.

In the beginning, Katz did most of his work at Hildegard’s kitchen table. They hired an answering service to handle the flood of phone calls, and offered Burg a job as a developer.

Colleagues were impressed by his intellect.

“He was extremely intelligent,” says Doug Hay, who joined the company in 1988 and stayed until June of last year. “He had all the equations from exams memorized from 10 years earlier, things you

generally forget 20 minutes after the test.”

Almost overnight, denizens of the bulletin boards switched from .arc compression to .zip in what became known as the arc wars.

System Enhancement sued PKWare in 1988 for copyright and trademark infringement. In 1989, as his legal costs mounted, Katz agreed to settle. Full terms of the settlement were not disclosed, but representatives of the New Jersey company may have been surprised when they finally met their nemesis.

“The lawyer for System Enhancement showed up at Hildegard’s house expecting a big company,” Kiehnau says. “He had an address from the bulletin boards, so he thought there would be a big glass building or something. It was really funny.”

Publicity about the lawsuit on bulletin board services nationwide helped fuel a backlash against System Enhancement, which accelerated the death of .arc as PKWare introduced new, incompatible archival tools with better compression algorithms.

Money poured in.

“Phil became a very wealthy man in a very short period of time,” Burg says. While Hildegard worked to keep business matters in check, Katz devoted nearly all his time to programming. He didn’t come to work until late afternoon and worked well into the night, so he could have complete silence and not have to interact with anybody, early PKWare employees say.

“He was rarely around. He did what he had to,” Kiehnau says. “If the business would have went belly up two years after it started, I don’t think he would have cared.”

But Katz’s unpredictable schedule frustrated his family. “They’d say ‘You have this business, and it’s growing. Why aren’t you here?” Kiehnau says.

During his frequent absences, Katz kept in touch with Hildegard and PKWare executives through electronic fax services. He oversaw product upgrades and revisions, and occasionally gave Hildegard instructions on business matters.

As his business grew, his personal life unraveled. Hildegard heard rumors her son was going to strip bars, cavorting with women and drinking heavily. She questioned him about his personal affairs, people who know the family say, and the relationship between the worried mom and wayward son began to fray.

They also squabbled when Katz tried to take money out of PKWare. He sometimes wanted as much as $25,000, Kiehnau says.

“He thought it was ridiculous that a 30-year-old man would have to beg his mother for a check from his own company,” Kiehnau says.

Katz grew bitter over his mother’s interference in his affairs. Eventually, he stopped talking to her altogether. The end came one day in 1995.

Hildegard received a fax informing her that her son planned a hostile buyout of her 25% equity stake. He had fired his own mother.

“It was like a funeral the day it happened,” Kiehnau recalls. “It was his product, but it was her business. (Kiehnau’s former wife) Cindi and I got called over to her house and she was crying and crying, ‘Why would Phil do this?’ “

That same year, Katz hired Robert Gorman as director of marketing and sales. Gorman had previously worked in sales for Frontier Technologies, a Milwaukee-based developer of Internet software.

Gorman maintains that Katz continued to manage the company, but others close to the situation say Katz’s day-to-day role was minimal. Although he signed off on major decisions and worked on product upgrades, the company was run by PKWare management, they say.

Despite the turmoil, PKWare’s business remained strong through the 1990s, says Richard Holler, executive director of the Association of Shareware Professionals in Greenwood, Ind. It is difficult to measure the company’s market share because not all shareware users end up licensing the product. But even as Windows-based “zip” products nibbled into PKWare’s sales, the company’s business held up, he says.

“They are still a big player in the commercial marketplace. They have a lot of ongoing relationships with other software developers that use the PKZip compression algorithm within their own products,” Holler says.

At the time of his death, Phil Katz was remembered among the world’s elite programmers for writing a truly revolutionary piece of software. But that single accomplishment, as significant and profitable as it was, couldn’t save Katz’s life.

Alcohol Takes its Toll

Katz talked freer, laughed harder, stayed up longer and dreamed bigger when he had a drink in his hand, friends say. Drinking brought a painfully shy man out of his shell.

“As soon as he started drinking, you could see a little smile on his face. That’s when he could talk to people, or tell a joke. When he didn’t drink, he would pick jokes apart. He would think really deep

and wouldn’t have as much fun,” says Fischer, the dancer who met Katz in 1994 and grew fond of him.

But the alcohol was ripping his life from its moorings.

On May 7, 1991, as he was driving his 1990 Nissan 300ZX with plates that read PKWARE, a police officer ordered Katz to pull over. Katz was sitting in the driver’s seat, his glassy eyes nearly closed, according to the police report. He was convicted of operating under the influence of an intoxicant.

It was the first in a torrent of legal troubles.

About a year later, Katz was again convicted of drunken driving. Between 1994 and September 1999, Katz was arrested five times for operating after suspension or revocation of his license. Records show that courts issued six warrants related to his driving, including two for bail jumping.

Once the authorities starting looking for him, Katz started showing up at work a lot less often.

“He just disappeared,” Hay says. “Sometimes you would see him at trade shows, but that was about it.”

When Katz did go to work, the strain was evident, former employees say. “He lived in a state of paranoia,” says one former employee, who asked not to be identified. “He thought that (WITI-TV Channel 6) across the street from us was watching him.”

Katz knew that if authorities were looking for him at PKWare, they probably were also trying to find him at the handsome, brown-brick luxury condominium he owned near Mequon Country Club.

His neighbors, unaware of his legal problems, were baffled by Katz’s reclusive nature. Many say they had never seen or met Katz even though he supposedly had lived there for almost five years.

“I never saw a light on, I never saw tire tracks in his driveway, and I live across the street. It was almost spooky,” says Peter Picus, a neighbor.

The condominium was in the eye of a publicity storm in August 1997 after neighbors complained about a stench emanating from the home and mice and insects scurrying near the unit.

Mequon authorities obtained a search warrant to enter the condominium, after neighbors and inspectors were unable to locate Katz. They found a stinking mass of garbage, sex magazines, videos and sex toys like whips and chains, according to Kenneth Metzger, former general sanitarian for the City of Mequon.

“It was a mess. I had been in the business for more than 40 years, and it was one of the worst that I had seen,” Metzger says. “It was knee deep in garbage. There were bottles, cans and rotting fast-food stuff all over the place. Whatever happened to that man, he went off the deep end.”

Though Metzger and his crew knew little about the evasive Katz, they could tell that he was wealthy. Among all the rubbish, they found credit cards, money, a laptop computer and jewelry that had never

been opened.

Publicity about the discoveries hurt Katz deeply, friends say, and some say it marked the beginning of the end.

“When they raided his house, they exploited it and told everybody at his company about his fetish. His mother found out, everybody found out,” Fischer says.

“He knew people would jump to conclusions about him,” she says. “He felt really violated. That’s the day he completely stopped going into PKWare. He didn’t want his personal life mixed in with his

employees. Nobody really does.”

By this time, Katz’s closest acquaintances were the dancers at the strip bars he frequented.

Fischer says Katz showered her and other dancers with gifts, often taking groups of them with him to Las Vegas. Several of them accompanied him to the 1998 Comdex computer show there.

“I would sleep with him in the same bed. He never would touch or sneak a peek or anything like that,” she says. “Sometimes he would cry and be like, ‘Hold me, Chastity.’ You’d just have to hold him

all night long.”

“There was never anything dirty about him,” she says. “He was not a pervert. I swear on my Bible. He was the most harmless, most generous, unselfish guy I have ever known.”

Some of his stripper friends took advantage of his generosity, stealing his credit card numbers and buying things for themselves. It intensified his paranoia. Katz began to keep any receipt or piece of mail bearing his name or account numbers. He piled it all into the back of his 1991 Nissan Pathfinder.

“That Pathfinder was so disgusting. It literally had no back seat,” Fischer says. “It was papers from the ground up.”

Fearful of the arrest warrants, Katz kept on the move. In addition to the drunken-driving convictions, he had a half-dozen judgments against him from financial institutions totaling more than $30,000, court records show.

Katz hopscotched along a strip of hotels near Mitchell International Airport, staying at one for three or four days, then moving to the next, usually less than a few hundred yards away.

“You know what he did? He sat in his hotel room every single day,” Fischer says. “The only time he got out of the hotel room was maybe to go have dinner.”

Fischer says Katz sometimes called her answering machine late at night, pleading with her to join him. During their conversations, he sometimes spoke candidly about his family, his company, and his childhood, Fischer says.

He said that his separation from his mother and sister was difficult, and that he continued to send Hildegard flowers and e-mails, even though they hadn’t talked since he fired her from the company.

Through it all, Katz drank heavily.

Fischer says he drank at least a liter of Rumple minze and two bottles of Bacardi rum a day.

“He would drink until he’d puke. We’d have to see this. I never was with an alcoholic where you’d have to see it. After a while it was starting to make us sick,” Fischer says. “We’d say Phil, you know, this is sickening. You’re killing yourself, and we’re watching you do it.”

Hildegard Katz says her son underwent treatment for alcohol abuse. “We all tried to help. As with almost any alcoholic, the more you tell them to get some help, they begin to isolate themselves because they don’t want to hear it,” Hildegard says.

“I guess we really thought he turned the corner after he went through rehab.” But he had not turned the corner.

Fischer says she realized Katz was near the end when she visited him at a south side hotel a few weeks before his death. Clad in nothing but underwear, he was suffering from uncontrollable hiccups and burdened by a horribly swollen stomach.

“He took some Valium so he could sleep. That was the only time he could sleep,” she says. “Then he would have the alcohol shakes. I’d try to play computer games with him, but he’d run to the bathroom all the time.”

“He was so bad to the point where he would start (urinating) in his pants involuntarily. His liver was just going. He was puking up blood,” she says.

After helping Katz change his pants, Fischer left Katz’s hotel room.

She never saw him again.

Katz had been dead for two days before his body was found. PKWare employees learned of his death almost a week later.

In the days that followed, the company was flooded with hundreds of e-mails offering condolences from software junkies around the world. Most had never met Katz but were aware of what he had done. Stories of his death were printed in such far-flung media as the London Times, the New York Times and abcnews.com.

But the sadness was deepest for those who had suffered the longest as Phil Katz’s life came unglued. Hildegard had to make the sad trip to identify the son she hadn’t seen in five years.

Later, she reflected on the loss.

“I get the e-mails people are sending, and it is amazing how many people say that even though they never met him or talked to him they are ever grateful for what he did. One man said he saved my butt many times. Phil was concerned with helping people.

Appeared in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel on May 21, 2000.

http://www.packerplus.com/news/state/may00/katz21052000a.asp

As the modern workplace evolves, finding the talent your company truly needs to thrive can be difficult. First off, the skills we need to succeed in the modern workforce are not static. In fact, the most in-demand occupations and specialties did not exist ten years ago, and the pace of change is only accelerating.

But what’s more, old school hiring practices might be getting in our own way. While higher education and past experience are solid indicators of a good match for a role, there’s an increasing need for employers to verify applicant skills.

At LinkedIn, we recognize that reducing friction between highlighting, discovering and validating valuable job skills is an important step in facilitating economic opportunity. That’s why we launched LinkedIn Skill Assessments today– standardized, short-form assessments to help our members showcase select skills and stand out.

We surveyed 2,000 respondents in Employment in the US and 500 respondents who are involved in the Hiring Process in the U.S. to understand the importance both groups place on assessing, validating, showcasing, and learning new skills. Here are the highlights of what we found: Skills-based hiring is on the rise

Read more at:https://news.linkedin.com/

Here is a little snippet of the Google new home page. Not skewed at all ! And the picture is fuzzy because the issue is fuzzu.

George Carlin in one of his best and my at the top of my list.

Enjoy and leave a comment

DS

Well today was much better

And that’s that’s all I have to say about that.